Welcome to Freaky Friday, that one moment in the week when the truth about insects is revealed and you feel justified for having hated and feared them since childhood.

Insects—vital part of the ecosystem, or disgusting horrors bent on our destruction? Are they small miracles designed by God, or the vomit-inducing creeps who got tangled up in Kate Capshaw’s hair in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom? Could they be a vital part of tomorrow’s food chain, a high-protein, low-cost appetite buster? Or could they be horny monsters from Hell who want to gobble our junk? After reading a bunch of insect attack novels, I’m leaning towards the latter.

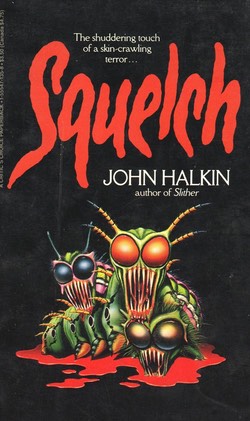

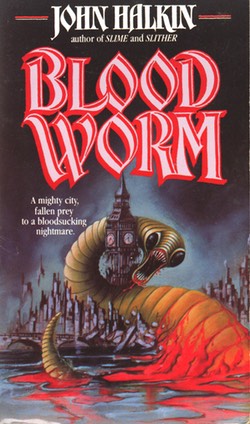

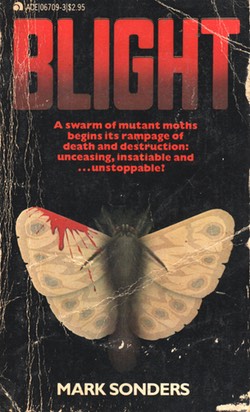

Whether it’s beetles and worms in John Halkin’s Blood Worm, caterpillars in his Squelch, or moths in Mark Sonders’s Blight, insects in horror fiction seem united in their plan to wipe humanity from the face of the Earth. Whenever I complain about how creepy spiders* are, it’s only a matter of time before some yoga dork carrying a copy of Zen Surfboards tells me that they aren’t eight-legged horror shows with too many eyes and no social skills but are instead a vital link in the food chain that maintains the integrity of Gaia. Maybe, but I wish that whenever a caterpillar started ranting about wiping mankind from the planet there was another caterpillar with a gluten allergy and a blue mat rolled up on its back to say the same about humans.

*Yes, I know spiders aren’t technically insects but they are just as liable to invade England as moths, so they’re basically insects.

So what do we learn about insects in these three novels? First off, insects are so excited to murder us all that they’re eating the guts of a hobo by page 8 of Blood Worm, chewing off the face of a bulldozer driver by page 6 of Blight, and burrowing into the belly button of a small boy by page 9 of Squelch. Insects hate us so much that the moment we genetically mutate them they stop looking at us as their masters and start regarding us like mobile buffets.

The most politically relevant of the three is Blood Worm (1988), whose cover explains the Brexit vote in one simple image. Like a team-up between ISIS and Al Qaeda, Blood Worm posits a London in which multicolored beetles with razor sharp claws and an endless appetite for human flesh join forces with blood worms who like to burrow into the guts of helpless bystanders and gorge themselves on our vital organs. As these long, tapering worms grow excited and eat our flesh they become engorged, turning bright red and swelling to enormous size, so basically London is under attack by a horde of thinly veiled phallic symbols. Who have eyes. “A long, pale, snake-like thing fed on his exposed throat. It looked up and stared at George with hard eyes, the blood slobbering from its hideous mouth.”

The most politically relevant of the three is Blood Worm (1988), whose cover explains the Brexit vote in one simple image. Like a team-up between ISIS and Al Qaeda, Blood Worm posits a London in which multicolored beetles with razor sharp claws and an endless appetite for human flesh join forces with blood worms who like to burrow into the guts of helpless bystanders and gorge themselves on our vital organs. As these long, tapering worms grow excited and eat our flesh they become engorged, turning bright red and swelling to enormous size, so basically London is under attack by a horde of thinly veiled phallic symbols. Who have eyes. “A long, pale, snake-like thing fed on his exposed throat. It looked up and stared at George with hard eyes, the blood slobbering from its hideous mouth.”

The blood worms and beetles destroy a large number of fine old buildings, before chewing the guts of a large number of children, men, women, fire fighters, and police officers before everyone flees London, abandoning it to the inevitable post-apocalyptic motorcycle gangs. Then the Royal Air Force drops napalm on the city and burns it to a cinder. Then they dose the cinders with a bio-engineered virus. The only way to save London is to destroy it, although, as one character observers, “We can never really be certain.” Which is true. Considering that this book came out in ’88, the blood worms might have merely burrowed underground, woven cocoons, and emerged later as the Spice Girls.

No one’s sure about the origins of Blood Worms n’Friends in Blood Worm but the danger in Blight (1981) has a clear source: John Stole, real estate developer and terrible human being, who discovers that his latest purchase of hundreds of acres of real estate is the breeding ground for moths, leading him to reflect, “This area had once been a protected area of sorts. But with the proper palms greased, who really cared about moths? So this was their natural feeding site. So what? They’d find someplace else to feed.” Like your face.

If his disregard for the environment isn’t enough to get your rage up, he’s also 27 years old and “paunchy.” Is there any character more hateful than an entitled millennial with a gut who doesn’t care about moth sex? But Stole’s spraying of insecticide over the moth’s happy humping lands has turned them into mutant moths which, I’ll admit, is not an inherently scary idea. Even a giant moth, like Mothra, is hard to take seriously, and Mothra had two tiny princesses to sing back-up. As one character says, “It still doesn’t make sense to me. Moths attack sweaters and fly around light bulbs. They don’t devour humans.” And yet they do. And they fly into ears, up noses, down throats, and, unfortunately, up butts. So, while one Mothra may not be very scary, this book suggests that many moth(ra)s are terrifying.

If his disregard for the environment isn’t enough to get your rage up, he’s also 27 years old and “paunchy.” Is there any character more hateful than an entitled millennial with a gut who doesn’t care about moth sex? But Stole’s spraying of insecticide over the moth’s happy humping lands has turned them into mutant moths which, I’ll admit, is not an inherently scary idea. Even a giant moth, like Mothra, is hard to take seriously, and Mothra had two tiny princesses to sing back-up. As one character says, “It still doesn’t make sense to me. Moths attack sweaters and fly around light bulbs. They don’t devour humans.” And yet they do. And they fly into ears, up noses, down throats, and, unfortunately, up butts. So, while one Mothra may not be very scary, this book suggests that many moth(ra)s are terrifying.

These tiny death dealers make a reappearance in Squelch (1985) when a horde of enormous moths flutter over to dear old England, which seems to hold the same appeal for bloodthirsty insects that Japan holds for giant monsters. Squeaking like bats, the moths unroll their savage proboscises and begin to suck the blood of humans. Ginny, a TV director, fired for taking a moral stand against scenes of a gas chamber being cut out of an afternoon drama she directed for the BBC, is living in the country near her sister and brother-in-law when the moths invade, spitting poison and sucking blood, then disappear. A year later their children crawl out of the soil: stinging, poisonous caterpillars who stage ambushes at school fairs and church services, use their plump squooshy bodies to form dead caterpillar slicks on highways, and generally suck the blood of this once-great nation, freeloading off the fat of its citizens.

Whenever a character in Squelch has a shock they’re encouraged to take a drink, sometimes several drinks per hour given the number of shocks per second they experience, so it’s no surprise that their resistance to the caterpillars is nominal. It’s also no surprise that in their inebriated state they decide to fight the caterpillar invasion with a lizard invasion, importing enormous monitor lizards from Africa. Yes, the five-foot-long lizards eat the caterpillars but then they’re stuck with an island overrun by enormous lizards. As the final page rolls around, Ginny sits in her caterpillar-free house — albeit a home covered in huge, darting lizards — wondering if this might have been a mistake.

Weirdly enough, the insect apocalypse seems to bring out the horndog in everyone. After her sister has half her foot gnawed off by a hungry caterpillar, Ginny feeds her a medicinal whiskey then leaps into bed with her husband. In Blood Worm, the main character’s wife sleeps with a number of men during the infestation then leaves a note saying that she’s a slut and, by the way, their daughter is missing. She immediately becomes an alcoholic hobo, and is last seen stumbling around the ruins of London. Although I can’t blame the characters when the insects seem to be so focused on our genitals. “The constable lay on his back,” Halkin writes in Squelch. “His body twisting as though in a fit, caterpillars probing every part of him. Over the groin the blue serge of his uniform trousers was soaked in blood. Two caterpillars had eaten their way through it—from the inside…”

Perhaps insects are simply in love with us, but without the properly-sized appendages they cannot hug us or hold us, but merely chew us and gnaw us? Or, in the case of the moths of Blight, as one young mother surrenders herself to being sucked to death by their proboscises, “They could hurt her no more. They had done their worst. Or so she thought. An intense slice of pain, unlike any she had ever before experienced, made her body jerk upright into a sitting position as the moths attacked and conquered areas obscenely tender and private.”

Attacking and conquering our obscenely tender and private areas, insects are like terrible dates who don’t just leave us drained of blood and covered in bore holes, they also leave us full of their eggs, and feeling barfy. I’ll take Japan, where at least you know where the monsters are hiding.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, just came out this past Tuesday. It’s basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.